The Architecture of Invisible Rules: An Anthropological and Practical Analysis of Social Conduct in the Kingdom of Morocco

1. Introduction: The High-Context Crossroads of the Maghreb

The Kingdom of Morocco, the westernmost outpost of the Islamic world (Al-Maghreb al-Aqsa), presents the visitor with a sensory and cultural complexity that belies its geographical proximity to Europe. Separated from Spain by a mere 14 kilometers of the Strait of Gibraltar, Morocco occupies a unique liminal space where the indigenous Amazigh (Berber) foundations are overlaid with Arab-Islamic traditions, Andalusian refinement, and a persistent French colonial administrative legacy. For the international observer, particularly those from “low-context” cultures such as the United States or Northern Europe—where communication is explicit, and rules are codified in signage—Morocco functions as a “high-context” society. Here, meaning is embedded in the situation, the relationship, and the silence between words rather than in the words themselves.

The casual tourist often perceives Morocco through the lens of exoticism: the chaotic vibrancy of the souks, the serenity of the Sahara, or the architectural splendor of the riads. However, beneath this aesthetic surface lies a rigid, ancient architecture of social conduct. These unwritten rules govern everything from the exchange of money to the breaking of bread. Violating them rarely results in direct confrontation, for Moroccan culture values the preservation of face and social harmony. Instead, the transgressor is met with a withdrawal of genuine Diyafa (hospitality), replaced by a transactional and often exploitative interaction.

This report provides an exhaustive analysis of seven critical, non-obvious rules of conduct. These rules, derived from a specific travel advisory and expanded through deep sociological research, are not merely etiquette tips but windows into the Moroccan soul. To understand why one must not refuse tea is to understand the history of British trade and local agriculture. To understand the prohibition on using the left hand is to engage with Islamic theology and historical hygiene practices. By mastering these invisible architectures, the visitor transitions from a transient source of capital to an honored guest, accorded the protections and warmth that define the true Maghrebi experience.

2. The Economic Ritual of Baksheesh: Gratitude as Social Security

The first rule identified in the source material is the imperative: “Do Not Forget to Tip.”. To the uninitiated, the constant friction of small payments in Morocco can feel like aggressive solicitation or “tipping culture” gone awry. However, an anthropological examination reveals that the practice of Baksheesh is a sophisticated, informal wealth-redistribution system that underpins the service economy.

2.1 The Etymology and Sociology of Alms

The term Baksheesh is linguistically rooted in the Persian bakhshish (to give) and the Sanskrit bhiksha (alms). In the Moroccan context, it operates at the intersection of three distinct social concepts:

- Sadaqa (Voluntary Charity): A pious act in Islam intended to purify one’s wealth and earn spiritual merit (Baraka). Giving to the poor is not just aid; it is a spiritual transaction.

- Haqq (Right/Due): In the service sector, where base wages are often nominal or non-existent, the tip is viewed not as a bonus for excellence but as the worker’s “right” for the labor performed.

- Rashwa (Bribery): While Baksheesh can veer into corruption in bureaucratic settings, for the tourist, it remains largely within the realm of service facilitation.

Historically, this system acted as a social safety net. In the absence of state welfare, the wealthy (and now the tourist) are expected to subsidize the livelihood of the service class. Refusing to tip is not interpreted as “thrifty” but as a violation of the social contract—a rupture in the flow of Rizq (sustenance provided by God).

2.2 The Phenomenon of the Gardien de Voiture

Perhaps the most confounding aspect of this economy for Western drivers is the Gardien de Voiture (Car Guardian). In every Moroccan city, from the boulevards of Casablanca to the dusty lots of Zagora, men wearing reflective vests (often with official badges) manage parking spaces.

These guardians are not beggars. They are part of a highly organized, territorial labor sector. They effectively “rent” the right to manage a street from local authorities or informal neighborhood networks.

- The Service: They assist in parking (signaling with complex hand gestures), cover windshields with cardboard to protect against the sun, and, crucially, watch the vehicle to prevent theft or vandalism.

- The Rule: Payment is mandatory. It is not a gratuity; it is a fee.

- The Rate: Standard rates are 2 to 3 MAD for short daytime stops and 5 to 10 MAD for overnight parking.

- The Consequence: Refusing to pay is seen as theft of service. While physical confrontation is rare, verbal abuse is common, and the social order of the neighborhood supports the guardian’s claim.

2.3 Comprehensive Tipping Guide (2025 Standards)

The following table outlines the expected gratuities across various sectors, reflecting the economic realities of 2025.

| Service Provider | Context | Recommended Amount (MAD) | Sociological Insight |

| Café Server | Coffee/Tea (10-15 MAD) | 1–2 MAD per person | “Keep the change” is insufficient if the bill is exact. The coin must be visible. |

| Restaurant Waiter | Meal | 10% – 15% of bill | Wages are low; servers often share tips with kitchen staff (the tronc system). |

| Petit Taxi Driver | Inner-city travel | Round up to nearest 5 or 10 | Drivers rent their vehicles daily (recette); margins are razor-thin. |

| Hotel Porter | Luggage handling | 20–30 MAD total | Medina porterage involves heavy physical labor over uneven terrain/stairs. |

| Riad Staff | Housekeeping/Cooks | 50–100 MAD per room/stay | Often placed in a communal box at the end of the stay to ensure equitable distribution. |

| Guide (Official) | Full Day Tour | 200–300 MAD | Acknowledges not just the tour, but the protection from harassment provided by the guide. |

| Driver (Intercity) | Multi-day trips | 150–200 MAD per day | Usually given as a lump sum at the end of the trip as a gesture of gratitude. |

| Public Toilet Guardian | Restrooms | 1–2 MAD | Mandatory. Pays for cleaning supplies and the guardian’s presence. |

| Gas Station Attendant | Pumping/Windows | 2–5 MAD | Self-service stations are rare; this is a labor-intensive service role. |

2.4 The Logistics of Generosity

Travelers often fail this rule not out of stinginess, but out of logistical unpreparedness. Morocco is a cash-heavy society.

- The “Small Change” Crisis: Large bills (100 or 200 MAD notes) are useless for tipping. A seasoned traveler hoarding coins (1, 2, 5, 10 MAD) is essential. Breaking a large bill at a small kiosk to generate change is a daily ritual.

- The Exchange: Tipping is rarely done discreetly in a handshake (as in some Western luxury contexts) but is left openly on the table or tray. However, handing a tip directly to a person should be done with the right hand and a smile, acknowledging the human connection.

3. The Sacred Pour: The Tea Ceremony as a Binding Social Contract

The second non-obvious rule is the stricture: “Do Not Refuse Tea.”. To view Moroccan Mint Tea (Atay) merely as a caffeinated beverage is to fundamentally misunderstand its role in Maghrebi society. It is the primary vehicle for social bonding, conflict resolution, and hospitality.

3.1 Historical Origins: “The Moroccan Whiskey”

Paradoxically, tea is a relatively recent addition to Moroccan culture. While mint has been cultivated for millennia, tea leaves arrived in the mid-19th century (circa 1854) during the Crimean War. British merchants, blocked from their usual Baltic markets, sought new buyers for Chinese Gunpowder tea (green pearl tea) and found a willing market in Morocco. The locals adapted the bitter brew by adding their indigenous fresh spearmint (Nana) and generous amounts of sugar, creating a high-calorie stimulant that aligned with Islamic prohibitions on alcohol—hence the playful moniker “Moroccan Whiskey” or “Berber Whiskey”.

3.2 The Anatomy of the Ritual

Unlike cooking, which is traditionally the domain of women in Moroccan households, the preparation of tea for guests is often performed by the male head of the household. This public performance serves as a demonstration of skill and honor.

The Ingredients and Tools

- Gunpowder Tea: Chinese green tea rolled into small pellets that “explode” when steeped.

- Fresh Mint: Huge bunches of spearmint (or wormwood/sheba in winter) are used, stems and all, not delicate sprigs.

- The Sugar Loaf (Pain de Sucre): Traditionalists use solid cones of sugar, broken with a brass hammer. The quantity is staggering to Western palates—often 50-100 grams per pot.

- The Berrad: The iconic curved metal teapot, designed to be placed directly on charcoal embers.

The Performance of the Pour

The defining visual of the ceremony is the high pour. The host lifts the teapot two to three feet above the glasses. This is not mere theatricality; it serves three functional purposes:

- Oxygenation: It aerates the tea, smoothing the bitterness of the tannins.

- Cooling: It brings the boiling liquid to a drinkable temperature.

- The Reza (Turban): The high pour creates a thick layer of foam on the surface. A glass without this foam is considered “bald” and poorly prepared. The foam prevents the tea leaves and mint from entering the mouth and is a sign of the host’s mastery.

3.3 The “Three Cups” Rule and Temporal Commitment

Accepting tea is an acceptance of time. It is impossible to drink hot tea quickly, and thus the ritual enforces a pause in the frantic pace of life. A famous Maghrebi proverb dictates the progression of the flavor profile:

“The first glass is as gentle as life, The second is as strong as love, The third is as bitter as death.”

- Glass 1: The mildest, as the sugar has not fully dissolved and the tea is freshly steeped.

- Glass 2: The peak flavor, sweet and minty.

- Glass 3: The strongest, as the tannins from the Gunpowder tea have fully released, providing a bitter, caffeine-heavy finish.

3.4 The Etiquette of Refusal

Refusing tea is seen as a rejection of the host’s Baraka (blessing) and protection. In the context of a shop, refusing tea can stall negotiations, as the tea establishes the rapport necessary for commerce.

- The Strategy for Non-Drinkers: If health reasons (diabetes) prevent participation, one must be explicit: “Fiya as-sukkar” (I have diabetes). Even then, it is polite to accept the glass, hold it to warm the hands, and perhaps wet the lips without drinking deep. Total refusal without explanation is a grave insult.

4. The Lens and the Law: The Politics of Images and Privacy

The third rule, “Do Not Photograph People Without Permission,” is a complex intersection of traditional beliefs regarding the soul and modern privacy legislation modeled on French law.

4.1 The Anthropology of the Image: The Evil Eye

In rural areas and among the older generation, the camera is viewed with suspicion. This is rooted in the concept of l’ayn (the Evil Eye). The belief holds that an envious or admiring stare can cause misfortune. A camera lens, which fixes a stare permanently, is seen as a mechanism that might capture a fragment of the soul or attract negative spiritual attention.

- The Sanctity of Women: Photographing women is particularly sensitive. In traditional Moroccan society, the domestic sphere is the Harem (forbidden/sacred). A woman’s image belongs to her family. A stranger capturing it is a violation of her privacy and honor. Unauthorized photography of women can lead to immediate, aggressive public shaming by male bystanders.

4.2 The Legal Framework: Droit à l’Image

Modern Morocco enforces strict privacy laws (Law 09-08).

- The Law: Publishing a photograph of an individual without their consent is a criminal offense if it harms their reputation or privacy. While “street photography” of crowds is generally tolerated, focusing on a specific individual without a release form opens the photographer to civil and criminal liability.

- The Penalty: Fines and confiscation of equipment are common. Police will almost always side with the local citizen who claims their privacy was violated.

4.3 The National Security Red Lines

The prohibition extends aggressively to the state. Morocco is a security-conscious state.

- Forbidden Subjects: It is strictly illegal to photograph:

- Police officers and military personnel.

- Royal Palaces.

- Government buildings (courts, parliament).

- Infrastructure (dams, bridges, airports).

- Consequences: Tourists snapping photos of police checkpoints have been detained, interrogated, and had their memory cards wiped. This is not a “cultural” faux pas; it is a security violation.

4.4 The Drone Prohibition: A Total Ban

One of the most crucial pieces of information for modern content creators is the absolute ban on drones.

- Import: You cannot bring a drone into Morocco. Customs officers at all airports (Casablanca, Marrakech, Tangier) scan all luggage specifically for drones.

- Confiscation: If found, the drone is confiscated. You are issued a receipt and may be able to retrieve it upon departure, but this involves paying storage fees and navigating complex bureaucracy. Many travelers never see their equipment again.

- Usage: Flying a smuggled drone is a serious offense that can lead to espionage charges.

4.5 The Economy of the Image

In tourist hubs like Djemaa el-Fna in Marrakech, photography is a transaction. The snake charmers, water sellers (Gerrab), and Gnawa musicians are performers.

- The Rule: If you take a photo, you must pay. Snapping a “sneaky” photo is viewed as theft of their intellectual property.

- The Protocol: Negotiate the price before raising the camera. A standard fee is 10–20 MAD. Failing to pay will result in aggressive harassment.

5. The Gaze and the Gendered Sphere: Navigating Hshuma

The fourth rule advises women: “Do Not Look Strangers Directly in the Eyes.”. This directive is often jarring for Western women for whom direct eye contact signals confidence and honesty. In Morocco, the semiotics of the gaze are governed by gender and Hshuma.

5.1 The Concept of Hshuma (Shame)

Hshuma is the governing force of Moroccan social behavior. Unlike Western “guilt cultures” (internal conscience), Morocco is a “shame culture” (external judgment). Hshuma encompasses behaviors that are socially unacceptable, embarrassing, or modest.

- The Application: Losing face, causing someone else to lose face, or violating gender norms is Hshuma. It is the mechanism that maintains social order without police intervention.

5.2 The Semiotics of Eye Contact

- Man to Man: Direct eye contact is essential. It signifies truth (Haqq) and respect. Looking away implies shiftiness.

- Woman to Man: In the traditional code, a modest woman lowers her gaze (ghadd al-basar). Prolonged direct eye contact from a woman to a man is culturally interpreted as a sign of sexual interest or availability. It breaks the barrier of modesty.

- The Consequence: Female tourists who smile and make eye contact with men on the street often complain of harassment. They are unknowingly sending a signal that is read locally as an invitation.

- The Strategy: The most effective tool for female travelers is dark sunglasses. They allow the traveler to observe the surroundings without engaging in the “transaction” of the gaze. Walking with purpose and ignoring catcalls (“invisible mode”) is the standard local strategy.

5.3 Public Displays of Affection (PDA)

PDA is strictly Hshuma. Kissing or heavy petting in public is not only culturally offensive but can be legally prosecuted as “offending public morals.” Hand-holding is acceptable for married couples, but even this is rare among conservative locals. Conversely, holding hands between men is common and signifies friendship, not homosexuality.

6. The Right Hand of Purity: Theology and Hygiene

The fifth rule, “Do Not Use Your Left Hand,” is absolute. It applies to eating, greeting, and handing over money. This is not merely an arbitrary mannerism; it is a theological imperative rooted in Islamic hygiene.

6.1 The Theology of the Hand

In Islamic tradition, derived from the Sunnah (practices of the Prophet Muhammad), the body is divided into zones of purity.

- The Right Hand (Yamin): Reserved for noble tasks—eating, holding the Quran, shaking hands, giving gifts.

- The Left Hand (Shimal): Reserved for Istinja—the act of cleaning the body after using the toilet.

- The Taboo: To offer the left hand to someone is to offer them filth (Najis). To eat with the left hand is, according to Hadith, to “eat as Satan eats”.

6.2 The Ritual of the Communal Dish

Moroccan dining is communal. A single large platter (Tagine or Couscous) is placed in the center of a low table.

- The Invisible Geometry: The platter is conceptually divided into pie slices. Each diner must eat only from the triangle directly in front of them.

- The Mechanics: Eating is done with the right hand, using the thumb and first two fingers. The bread (Khobz) acts as the utensil (the scoop).

- The Violation: Reaching across the platter to another person’s section is considered greedy and disgusting. It violates the boundary of the shared space.

- The Meat: The meat is usually placed in the center of the dish. It is the prerogative of the host to distribute the meat to guests. Guests should eat the vegetables and sauce in their section and wait for the host to push a piece of meat toward them. Snatching meat from the center early in the meal is a grave breach of etiquette.

6.3 Handshakes and Interactions

When greeting, if the right hand is wet or dirty (from eating), a Moroccan will not offer the left hand. Instead, they will offer their right forearm or wrist for the other person to touch, or simply place their right hand over their heart and bow.

7. Khobz and Baraka: The Sanctity of Bread

The sixth rule, “Treat Bread with Respect,” highlights the spiritual status of food. In the West, bread is a side dish; in Morocco, Khobz is the vessel of life.

7.1 Bread as Divine Bounty

Bread is considered Niamah (a blessing from God). It possesses Baraka.

- The Taboo of Waste: Throwing bread in the trash is a sin. It implies ingratitude for God’s provision. It is culturally offensive to mix bread with general garbage.

- The Ritual of the Fallen Crust: If a piece of bread falls on the street, a Moroccan will stop, pick it up, kiss it, touch it to their forehead, and place it on a high ledge, wall, or tree branch. This removes the sacred object from the impurity of the ground and leaves it for birds or animals. It is an act of restoring order.

- Recycling: Uneaten bread is collected in separate bags and given to shepherds or beggars. In the medina, you will often see bags of stale bread hanging on doorknobs for collection.

7.2 The Sociology of the Farran

Every neighborhood has a Farran (communal oven). Before the proliferation of home gas ovens, families prepared dough at home and sent it to the Farran for baking.

- The Social Hub: The baker (Farnatchi) is a central figure in the neighborhood, knowing the secrets of every family by the quality of their bread.

- The Economy: Bringing bread to the communal oven costs a few dirhams and supports the local ecosystem. The Farran is also used to slow-cook dishes like Tanjia (the slow-cooked beef stew of Marrakech) in the cooling ashes.

7.3 Varieties of Moroccan Bread

| Name | Description | Consumption Context |

| Khobz | Round, flat, crusty loaf (semolina/wheat). | The daily staple; the “spoon” for Tagines. |

| Batbout | Pan-cooked, soft, pocket bread (like pita). | Used for sandwiches or breakfast. |

| Msemmen | Square, laminated, oily pancake. | Breakfast/Tea time; served with honey/cheese. |

| Baghrir | “Thousand-hole” spongy pancake. | Soaks up butter and honey; strictly for breakfast/tea. |

| Harcha | Pan-fried semolina biscuit-bread. | Crumbly texture; served with jam/cheese. |

8. The Informal Economy of Guidance: Faux Guides and Scams

The seventh rule, “Do Not Engage with ‘Voluntary Helpers’,” addresses the most persistent annoyance for tourists: the Faux Guide.

8.1 The Ecosystem of the Hustle

In the labyrinthine medinas of Fez and Marrakech, GPS signals often fail, and the streets are deliberately confusing. This creates a market for guidance.

- The Faux Guide: Usually young men, unemployed, who loiter at key intersections. They offer “help” that is never free.

- The Tactics:

- “The Road is Closed”: The most common scam. A young man will aggressively tell you the street ahead is closed (due to prayer, construction, or a dead end) to divert you toward a shop or a confusing route where you will need his paid assistance.

- The Tannery Scam: Leading tourists to “Berber tanneries” (often just a shop with a view) and demanding exorbitant fees for the “tour” or pressuring for purchases.

- The “Friendly” Student: Someone claiming to be a student who just wants to practice English. This interaction almost invariably ends in a shop or a demand for money.

8.2 The Brigade Touristique and Legal Risks

The Moroccan government takes tourism security seriously.

- Criminalization: Acting as a guide without a license is a crime punishable by jail time.

- The Police: The Brigade Touristique patrols the medinas in plain clothes. This is why faux guides will often walk five steps ahead of you or vanish suddenly.

- Official Guides: Real guides carry a large brass badge and an official license card. They are regulated and accountable.

8.3 Strategies for the Traveler

- Total Ignore: The most effective strategy is to avoid eye contact and keep walking. Engaging verbally, even to say “No,” signals that you are a potential target.

- “La, Shukran” (No, Thank You): A firm Arabic refusal is more effective than English or French.

- Ask the Right People: If lost, ask a shopkeeper (who cannot leave their shop to hustle you) or an older woman. Never ask a young man loitering on a corner.

9. The Gateway: Entry, Logistics, and “The Paradox of Tourism”

To contextualize the behavioral rules, one must understand the logistical framework of entering the Kingdom, as detailed in the source material.

9.1 Entry Requirements (Post-2022/2025 Context)

- Visa: Citizens of the US, EU, UK, Canada, Australia, and Russia (among others) do not need a visa for stays up to 90 days.

- Health: As of 2025, COVID-19 restrictions have been largely lifted, though travelers should always carry vaccination proof in case of sudden policy shifts. The “Health Form” mentioned in older advisories is generally no longer required for entry, but random checks can occur.

- Currency Restrictions: The Dirham is a closed currency.

- Import/Export Limit: You cannot legally import or export more than 2,000 MAD.

- Implication: You must exchange money upon arrival and spend it or convert it back before leaving. Attempting to leave with large wads of Dirhams can lead to confiscation.

9.2 The “Reasons Not to Visit” Paradox

The source material presents an ironic list of reasons to “never visit” Morocco, which serves as a rhetorical device to highlight its overwhelming richness.

- The “Simplicity” Trap: The ease of visa-free entry makes it deceptively accessible, luring travelers into a culture they may not be prepared for.

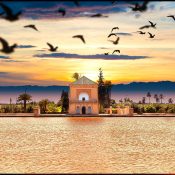

- Sensory Overload: The text warns of the “visual overload” of the Blue City (Chefchaouen) or the Red City (Marrakech), suggesting that the intensity of color and life makes the rest of the world seem dull by comparison.

- The Addiction of the Desert: The silence of the Sahara is described as a force that fundamentally alters the traveler, making it difficult to return to the “old self.” This aligns with the “high-context” nature of the country—it demands a surrender of Western temporal control.

10. The Sacred Trinity of Taboos: Politics and Religion

Beyond the seven social rules, there are three “red lines” in Moroccan discourse that carry significant legal weight. Freedom of speech is constitutionally protected but limited by the “sacredities”.

10.1 The King (Lèse-majesté)

The Monarchy is the central pillar of Moroccan stability. King Mohammed VI is not just a head of state but the “Commander of the Faithful” (Amir al-Mu’minin).

- The Law: Criticizing the King or the Royal Family is a criminal offense punishable by prison time.

- The Conduct: Never deface currency (which bears the King’s image). Avoid critical discussions of the monarchy in public spaces or on social media while in the country.

10.2 Islam and the Mosque Prohibition

Unlike in Turkey or Egypt, non-Muslims are strictly forbidden from entering mosques in Morocco.

- The Lyautey Legacy: This ban was codified by Hubert Lyautey, the first French Resident-General, to strictly separate French Catholic colonizers from Moroccan sacred spaces. It has been maintained by the Moroccan state to preserve the sanctity of worship.

- Maliki Jurisprudence: The Maliki school of Islam is strict regarding the ritual purity required to enter a prayer space.

- Exceptions:

- Hassan II Mosque (Casablanca): Open for paid guided tours (built partially as a monument to national craftsmanship).

- Tin Mal Mosque: (Currently under restoration post-earthquake).

- Mausoleums: Some shrine courtyards are accessible, but not the prayer halls.

10.3 Territorial Integrity (The Sahara Issue)

The status of the Western Sahara (referred to in Morocco as the “Moroccan Sahara” or “Southern Provinces”) is the third rail of Moroccan politics.

- The Stance: Morocco views this territory as an indivisible part of the Kingdom.

- The Risk: Referring to it as “Western Sahara” or displaying maps that show it as a separate country can lead to hostile interactions with locals and interrogation by authorities. Maps with the separation line are often confiscated at the border.

11. Conclusion: The Art of Being a Guest

Navigating Morocco requires more than a guidebook; it requires an adjustment of one’s internal clock and social expectations. The “rules” outlined in this report—from the nuanced economy of Baksheesh to the sacred theatre of the tea ceremony—are not barriers to enjoyment but the keys to cultural unlocking.

The tourist who tips the Gardien de Voiture is not being scammed; they are participating in the local social security system. The traveler who eats with their right hand is not just following a hygiene rule; they are signaling to their hosts, “I respect your purity, and I am clean enough to share your bowl.”

By adhering to these invisible architectures, the visitor sheds the armor of the outsider. They signal that they are not merely consumers of exotic images, but participants in the deep, ancient rhythm of Maghrebi life. In return, they are often granted the truest reward of Moroccan travel: the transition from Barrani (outsider) to Dayf (guest).

Summary of Key Directives & Cultural Drivers

| Rule | Action | The “Why” (Cultural Driver) | Consequence of Breach |

| 1. Tipping | Tip everywhere (Guardians: 2-5 MAD, Waiters: 10%). | Baksheesh is social insurance; Sadaqa (charity). | Hostility; seen as “theft of service.” |

| 2. Tea | Accept tea; drink 2-3 glasses. | Diyafa (Hospitality) confers honor on the host. | Rejection of friendship/peace offering. |

| 3. Photos | Ask permission; No drones; No police. | L’ayn (Evil Eye); Security State; Privacy laws. | Public shaming; confiscation; arrest. |

| 4. Eye Contact | Women should avoid staring at men. | Hshuma (Modesty); Avoiding sexual signaling. | Harassment; misinterpretation as invitation. |

| 5. Right Hand | Eat/Greet with RIGHT hand only. | Islamic purity (Sunnah); Left hand is for toilet. | Visceral disgust; seen as “unclean.” |

| 6. Bread | Never trash bread; place on ledge. | Baraka (Divine blessing) in sustenance. | Seen as arrogant and ungrateful to God. |

| 7. Guides | Ignore “Helpers”; use licensed guides. | Informal economy desperation vs. Rule of Law. | Scams; “Road Closed” diversion. |

| 8. Taboos | Respect King, Islam, & Sahara integrity. | National identity pillars & Criminal Law. | Legal prosecution; deportation. |

| 9. Mosques | Do not enter (except Hassan II). | Colonial legacy (Lyautey) & Maliki purity rules. | Ejection; offense to worshippers. |